The Engineer's Requiem: Lost Designs and Unfulfilled Potential in Slide Rule Innovation

The hum of a slide rule. The satisfying click as the scales aligned. For generations of engineers, mathematicians, and physicists, these sounds represented more than just calculation; they were a tactile connection to a legacy of ingenuity, a tangible manifestation of precision and problem-solving. Today, we celebrate the enduring appeal of the slide rule, but what of those designs, those innovations that flickered brightly and then faded into obscurity? This is the engineer’s requiem – a lament for lost potential, a look at slide rules that never quite found their audience or, tragically, were abandoned before their time.

The story isn't simply one of technological obsolescence. While the advent of digital calculators undoubtedly marked a pivotal shift, many of these discarded designs suffered from issues of complexity, cost, or simply, a lack of market demand in a rapidly evolving landscape. They represent not failures necessarily, but experiments, explorations of what *could* be, often displaying a remarkable level of craftsmanship and forward-thinking that deserves recognition.

The Early Pioneers: Beyond the Simple Duplex

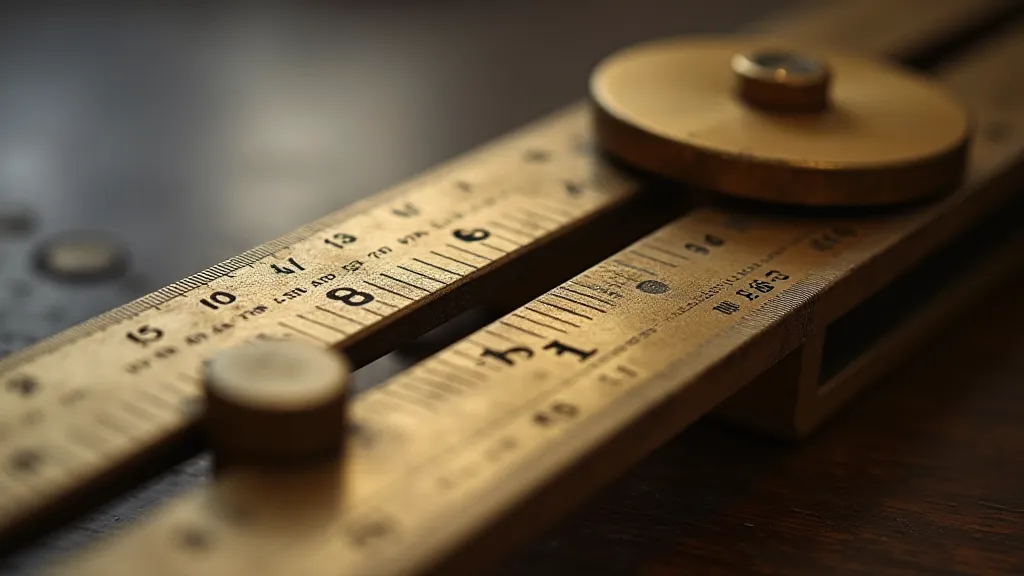

The basic duplex slide rule, with its C and D scales, was revolutionary, but it was just the beginning. Early pioneers recognized limitations. The need for more complex calculations – logarithms of logarithms, trigonometric functions, and more – quickly spurred experimentation. One of the earliest examples is the "Triple Scale" rule, dating back to the late 19th century. These rules attempted to incorporate a logarithm scale to the base 10, allowing direct calculation of log values. While conceptually sound, they suffered from being incredibly difficult to manufacture accurately. The intricate rulings required a level of precision that was costly and prone to error, severely limiting their adoption.

The Rise and Fall of the Circular Slide Rule

Perhaps the most visually striking of the discarded designs were the circular slide rules. These innovative devices, often appearing like miniature, ornate compasses, employed concentric circular scales to perform calculations. The advantage, in theory, was the ability to represent logarithmic values more efficiently, reducing the need for complex, stretched scales found on linear rules. Several companies, including Pickett and Eberhard, produced circular slide rules, and they were lauded for their elegance and perceived accuracy.

However, they faced significant hurdles. Manufacturing the precisely etched circular scales proved exceptionally challenging, driving up costs. Furthermore, the ergonomics were often awkward, requiring users to rotate the entire device, a less intuitive process than simply sliding a linear scale. While visually appealing and appealing to a niche market, the circular slide rule ultimately failed to displace the more established linear designs.

The Pickett Rath – A Glimpse of What Could Have Been

The Pickett Rath, introduced in the 1950s, stands out as a particularly intriguing example of unfulfilled potential. Designed by Captain James Rath, a noted engineer and slide rule enthusiast, the Rath boasted an unprecedented level of complexity. It incorporated, among other features, a built-in trigonometric scale with exceptionally high accuracy, a square root function directly on the main scales, and a unique “split C” scale that eliminated parallax errors inherent in many other designs. It was marketed towards naval architects and marine engineers.

The Rath's complexity, however, proved to be its undoing. It was significantly more expensive than other Pickett slide rules, and its operation required a steeper learning curve. Despite its technical merits, the Rath was discontinued relatively quickly, its innovative features deemed unnecessary by the vast majority of users. Today, it is highly prized by collectors as a testament to Pickett's ambition and Rath’s ingenuity.

The Era of "Super" Slide Rules: A Race for Complexity

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw a brief but intense period of "super" slide rule development. Companies like Faber and Eberhard were pushing the boundaries of what was possible, incorporating an astounding array of scales and functions. These “super” rules often featured logarithmic trigonometric scales, multiple square root scales, and even direct measurement of complex functions like the gamma function. They were beautiful, intricate machines, showcasing incredible engineering skill.

Yet, these efforts were ultimately futile. The digital revolution was looming. Why wrestle with a complex slide rule when a pocket-sized calculator could perform the same calculations with greater speed and accuracy? The cost of development and production, combined with the shrinking market, made these elaborate designs unsustainable.

The Human Element: Craftsmanship and a Sense of Loss

What’s particularly poignant about the story of these lost slide rule designs is the sheer craftsmanship involved. The ruling of the scales – the incredibly precise lines etched onto the surfaces – was a painstaking process, often requiring skilled artisans and specialized machinery. Each mark represented hours of labor and a dedication to accuracy that is rarely seen in today's mass-produced technology. The brass and ivory used in construction speak of a time when objects were built to last, with an emphasis on both functionality and aesthetics.

The disappearance of these designs also signifies a loss of a certain type of engineering thinking. The slide rule forced users to understand the underlying mathematics – to break down complex problems into manageable steps. It fostered a deeper appreciation for precision and a connection to the fundamental principles of science and engineering. The ease of digital computation, while undeniably beneficial, has arguably diminished this level of engagement.

Today, collectors seek out these abandoned designs not just for their rarity or monetary value, but for the story they tell – a tale of innovation, ambition, and the ephemeral nature of technological progress. Each slide rule, even those that never achieved widespread adoption, stands as a tangible reminder of a time when ingenuity and craftsmanship reigned supreme, and the simple act of calculation was a source of intellectual satisfaction.

The engineer’s requiem isn's a lament for failure; it's a celebration of the human spirit of invention and a reminder to appreciate the beauty and ingenuity of designs that, while lost to the mainstream, continue to inspire awe and admiration.